"The Chinese Room" by John Searle - No "mind" in a computer !

“Some years ago the philosopher John Searle badly shook the little world of artificial intelligence by claiming and proving (so he said) that there was no such thing, i.e., that machines, at least as currently conceived, cannot be said to be able to think. His argument, called sometimes the Chinese Room Thought Experiment, gained wide diffusion with an article in The New York Review of Books, and even penetrated the unlikely columns of The Economist.”

This is how Searle’s cognitive AI bomb – qualified a “storm” by author Elhanan Motzkin was introduced in the “The New York Review” on February 16, 1989.

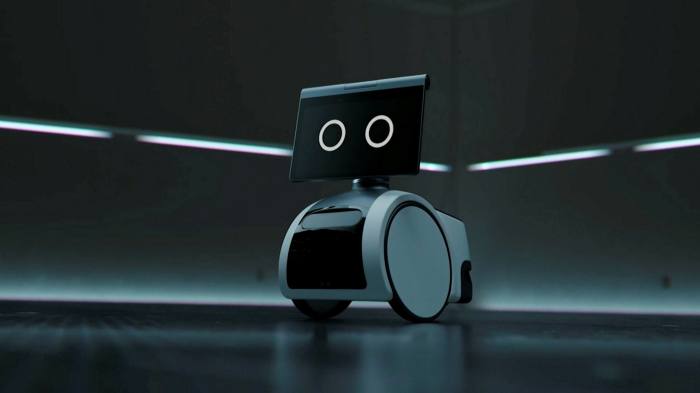

Searle’s objective : demonstrate against the Turing Test that one cannot attribute the ability to “think” to a machine, a computer or system like Siri, Alexa, Echo or Cortana.

On the only basis that answers of the programs are not distinguishable from those of an intelligent human speaker, is simply not good enough for the UC Berkley philosophy professor.

Searle’s Chinese Room argument has had large implications for semantics, philosophy of language and mind, theories of consciousness, computer science and cognitive science generally.

About "mind", "understanding" or "consciousness"

In 1980, Searle publishes “Minds, brains and programs” in the journal The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. He intends to demonstrate that a program cannot give a computer a “mind”, “understanding” or “consciousness”.

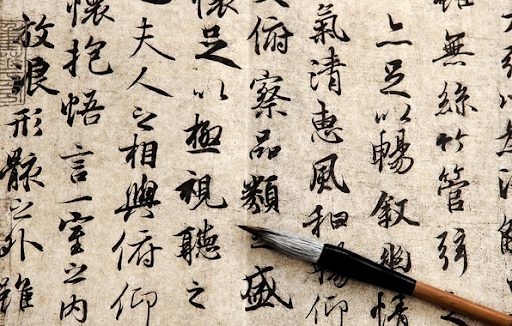

Searle criticizes the confusion of syntax and semantics.

Computers manipulate codes, follow syntactic rules.

However, they do not (yet) have access to the meaning (semantics) of the contents to which they seem to refer.

Searle’s “Chinese Room” proves that the purely syntactic representation of knowledge does not imply any understanding.

The possibility of “following rules” only means operating along formal processing steps (syntax), without understanding the meaning of the contextual facts (semantics).

John Searle explaining "The Chinese Room" argument

“The mind is to the brain as the program is to the hardware.”

“No matter how good the program, no matter how effective I am in carrying out the program, and no matter how my behavior simulates that of a Chinese speaker, I don’t understand a word of Chinese. and if I don’t understand Chinese on the basis of implementing the program, neither does any other digital computer on that basis, because that’s all a computer has.”

“The computer just manipulates formal symbols, syntax, syntactical objects, whereas mine has something in addition to symbols. It’s got meanings.”

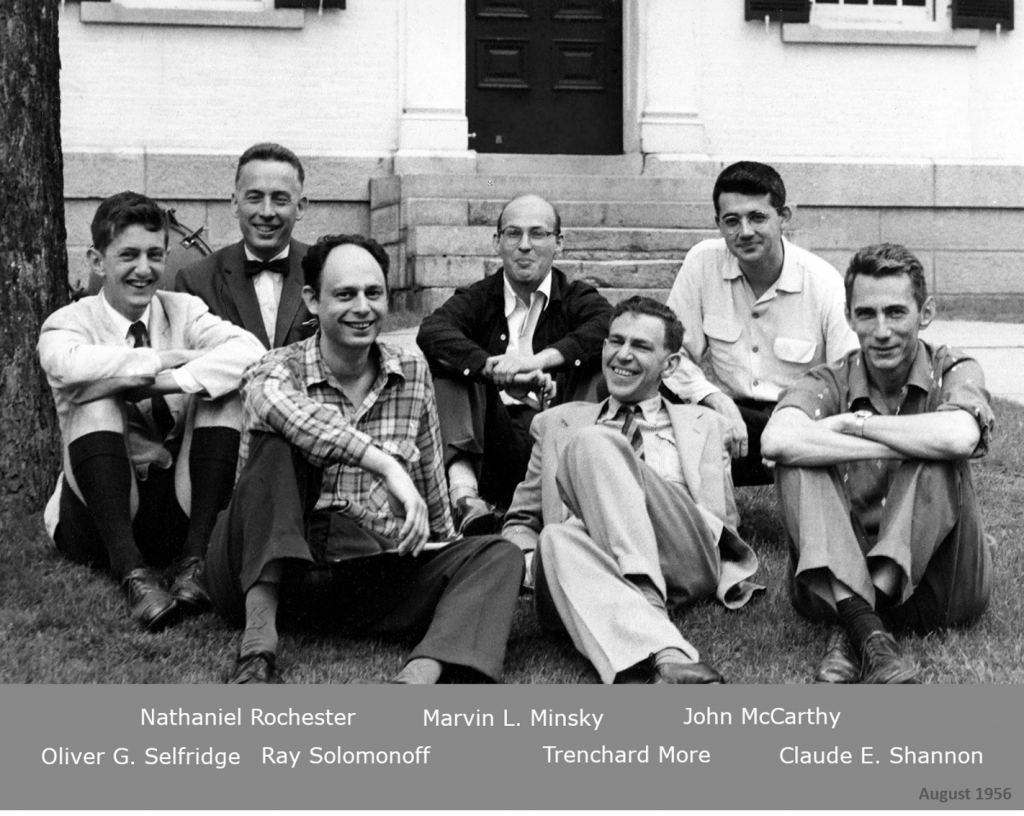

In the early 1950s, two directions of research

In the 1950s, the early days of AI research, two research

ideas were competing :

1) Cognitive : the idea of symbolic information processing to represent all the ideas of the world by formal reduction and then process them by computers. (cognitive and simulation). However not persued due to complexity.

“A human mind has meaningful thoughts, feelings, and mental contents generally. Formal symbols by themselves can never be enough for mental contents, because the symbols, by definition, have no meaning” – John Searle

2) Connectionist : “Brain-computer” metaphor based on an independently and self-learning computer (isomorphia computation and cognition). Neural networks, ML/ DL models.

In the 1950s, there was no real ethical concern about AI. The challenge was more technical.

The body-mind dualism

Besides the causal, and ontological questions, there are three aspects in the context of the body-mind dualism that are widely discussed these days.

First and foremost, Consciousness in machines, robots or autonomous programs. Currently, this aspect is mostly debated.

However, in the context of ethics and AI ethics, there are two remaining dimensions or levels of abstractions worth to consider : Intentionality and The Self.

Three aspects embodying the body-mind conundrum

- The question of consciousness: what is consciousness? When is there consciousness? If there is “artificial” intelligence, is there “artificial” consciousness? Can consciousness be instilled in a program? Can it be formalized? Can it be data-generated and processed by a program? If so, can a software program be the mind of hardware?

- The question of intentionality: what is intentionality? Is our conscious acting/programming an intentionality-by-proxy run on a computer?

- The question of The Self: what is The Self? Does a program have an identity? Does it have a soul? Do algorithms have a soul?

During the first years after releasing the thought-experiment, Searle was focusing exclusively on the consciousness issue.

Thirty years later, he gradually included the outmost importance of intentionality. With questions about accountability and responsibilty being debated, the question of intentionality has become crucial and intrinsiquely linked to the “mind” of computers.

Nowadays, we absolutely need to include the question of The Self, especially with identification issues of AI assistants. In robotics, the Three Laws of Asimov are no longer sufficient since a forth and a fifth law have been added, evoloving around “declaring its identity”. “Hello, I am a Google assistant making an appointement for Miss Fisher”.

Searle’s speech-act theory

⇒ Language performance does not imply thinking competence. Understanding.

The computer can close according to logical laws or between 0 and 1, distinguish, separate and classify and thus generate new logical knowledge in the computer.

The computer, however, can not choose and evaluate, thus generate relevant new knowledge without the understanding of humans.

Thus the argument that human minds are computer-like computational or information processing systems is refuted by Searle.

Instead minds must result from biological processes;

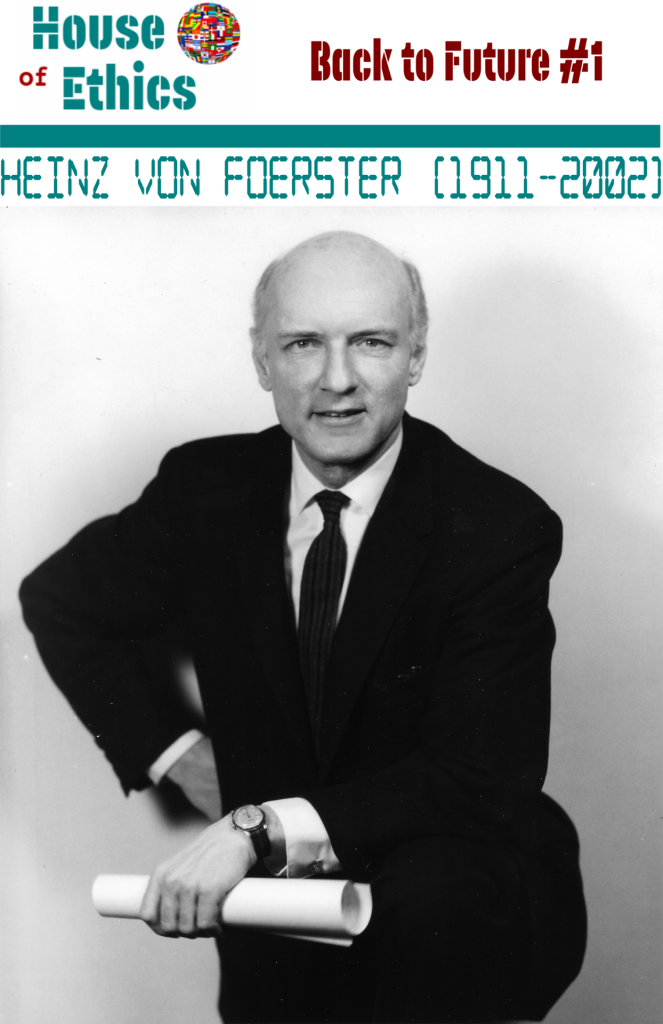

This is where Searle continues on the path of cognitive and systemic pioneers like Heinz von Foerster or Norbert Wiener or philosphers/linguists like Wittgenstein or linguists like Naom Chomsky.

Evolution of computer cognition : Cognitive computing and cognitive AI

Cognitive computing

Cognitive computing represents the Third era of computing

The First era, (19th century) with Charles Babbage, the ‘father of the machine’. The term “computer” was introduced by Alan Turing – before Turing a computer was called “machine”. ( e.g. Turing’s legendary question : Can machines think?).

The Second era (1950), experienced digital programming computers with Turing and Shannon, and programmable systems.

Now, the Third era, with cognitive computing with ML and DL models using learning algorithms and big data analytics.

“Cognitive computing represents self-learning systems that utilize machine learning models to mimic the way brain works.“

Cognitive AI

Yoshua Bengio, professor at the University of Montreal and winner of the prestigious Turing award for his work on deep learning, is one of the few recognized pioneers of machine learning (besides Yann LeCun and Geoff Hinton). He stipulates that AI needs perfecting.

Deep learning, as it is now, has made huge progress in perception, but it hasn’t delivered yet on systems that can discover high-level representations — the kind of concepts we use in language. Humans are able to use those high-level concepts to generalize in powerful ways. That’s something that even babies can do, but machine learning is very bad at.

As the scientific director of the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms (MILA), he is working on implementing the capabilities of, what he calls, “System 2” AI

“System 2” — slow, logical, sequential, conscious, and algorithmic, such as the capabilities needed in planning and reasoning.

“System 2” AI stands in contrast to “System 1” AI — intuitive, fast, unconscious, habitual, and largely resolved.

Understanding the world - understanding life - understanding high-level concepts

By 2025, experts predict a significant jump in the competencies demonstrated by AI. AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) is on everybody’s mind. Singularity has been predicted within the next 20 years.

But right now, for the most part, neural networks cannot properly provide cognition, reasoning and explainability.

Maybe or maybe not expected to reach the state of an autonomous artificial general intelligence (AGI), AI with higher cognitive capabilities will play a more assisting role in technology and business. Therefore ethical frameworks and legal regulations are paramount.

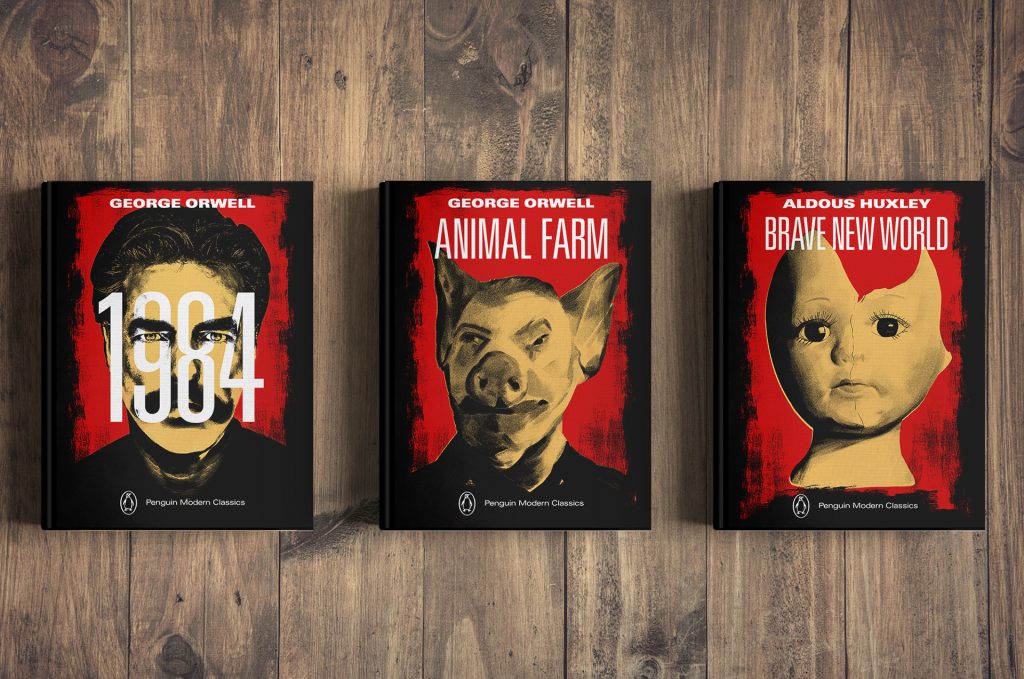

What would AGI be about? Understanding the world, understanding life and death.

Understanding the world goes far beyond connecting data. It goes beyond logic. It is about understanding high-level concepts. It is about understanding time, space, togetherness, care, respect, values. Being able to grasp paradoxes, contrasts, even the unfathomable.

Being capable of feeling beauty. Doing unrealistic, irrational things. Not being capable of explaining or fore-seeing, fore-feeling, intuitively uncertainty. Understanding the concept of Serendipity.

Being capable to tell a joke. To recognize nuances, humor. French humor, English humor, German humor, US humor, Swiss humor, Italian humor or Luxembourgish humor. They all are different. Nuancing irony, sarcasm, grotesque, absurdity.

Using idioms, metaphors, relating to mythical narratives. Feeling heritage. Feeling identity. Feeling the pleasure of eating an icecream or listening to a memorable tune.

Understanding, remembering intuitively, explaining, sensing, talking about la “Madeleine de Proust” in an article on Searle’s “Chinese Room”.

Lunatic? Yes!

But utterly human.

- Founder HOUSE OF ETHICS

- Author's Posts

Katja Rausch is specialized in the ethics of new technologies, and is working on ethical decisions applied to artificial intelligence, data ethics, machine-human interfaces and Business ethics.

For over 12 years, Katja Rausch has been teaching Information Systems at the Master 2 in Logistics, Marketing & Distribution at the Sorbonne and for 4 years Data Ethics at the Master of Data Analytics at the Paris School of Business.

Katja is a linguist and specialist of 19th century literature (Sorbonne University). She also holds a diploma in marketing, audio-visual and publishing from the Sorbonne and a MBA in leadership from the A.B. Freeman School of Business in New Orleans. In New York, she had been working for 4 years with Booz Allen & Hamilton, management consulting. Back in Europe, she became strategic director for an IT company in Paris where she advised, among others, Cartier, Nestlé France, Lafuma and Intermarché.

Author of 6 books, with the latest being “Serendipity or Algorithm” (2019, Karà éditions). Above all, she appreciates polite, intelligent and fun people.

-

The proposed concept of swarm ethics evolves around three pilars : behavior, collectivity and purpose

Away from cognitive jugdmental-based ethics to a new form of collective ethics driven by purpose.

Spécialisée dans l’éthique des nouvelles technologies, Katja Rausch travaille sur les décisions éthiques appliquées aux domaines tels l’intelligence artificielle, la data éthique, les interfaces machine-homme, la roboéthique ou la Business éthique.

Pendant 12 ans, Katja Rausch a enseigné les Systèmes d’Information au Master 2 de Logistique, Marketing & Distribution à la Sorbonne et pendant 4 ans les Data Ethics au Master de Data Analytics à la Paris School of Business.

Diplômée de la Sorbonne, Katja Rausch est linguiste et spécialiste en littérature du 19ème siècle. Partie à la Nouvelle-Orléans aux États-Unis, elle a intégré la A.B. Freeman School of Business pour un MBA en leadership et enseigné à Tulane University. À New York, elle travaille pendant 4 ans pour Booz Allen & Hamilton, management consulting. De retour en Europe, elle devient directrice stratégique pour une SSII à Paris où elle conseille, entre autres, Cartier, Nestlé France, Lafuma et Intermarché.

Auteure de 6 livres dont un dernier en novembre 2019, Serendipity ou Algorithme (2019, Karà éditions). Elle apprécie par-dessus tout les personnes polies, intelligentes et drôles.

- This author does not have any more posts.