Serendipity ou Algorithme

QUID SERENDIPITY ?

The word Serendipity is attributed to Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (1717-1797).

Philosopher and writer of Gothic novels including The castle of Otranto, he was also Member of the British Parliament, antiques dealer and salon man.

Contemporary to Voltaire, he only mentioned Serendipity once, … in a personal letter.

QUID ALGORITHM ?

The word Algorithm has been coined by the Persian mathematician and astronomer Al-WARIZMI or Al -KHOREZMI (around 780 -850).

The word “chiffre” and the discovery of the number zero have been attributed to him; he introduced the decimal system and became a pioneer of algebra.

The word Algorithmi, which is the Latin translation of Al-Khorezmi, eventually became Algorithm.

Why write about the mysterious Serendipity and the almighty algorithms?

Serendipity, as defined by its inventor Horace Walpole, is different from fate (positive and negative) or luck, providence, fortuity or pure chance.

Oddly enough, there is no theory or serendipitic manifesto, which makes the concept all the more intriguing.

The English Earl invented Serendipity while reading “a silly fairy tale” which was an English translation by a Frenchman who read “The Travels and Adventures of The Three Princes of Serendip”, a story by an unknown Persian author, in his turn inspired by Indian or Chinese folk stories (!!!). Mysterious and bizarre right from the start.

Inspired by travel literature, which was quite popular in the 18th century, Walpole invented the neologism Serendipity to describe the surprising adventures of the three young Princes of Serendip.

For Walpole, Serendipity was “a very expressive word”. Curious that Walpole only mentions Serendipity once in his writings – in a personal letter. Making us understand how tautologically serendipitic Serendipity is by comprising its own definition.

The two characteristic ideas of Serendipity, according to Walpole, are accident and sagacity. It’s connotations are esprit, attitude, perspective, receptivity, knowing how to connect, combine, reinterpret, reformulate, imagine and create.

Serendipity is an occurrence, a phenomenon, a positive circumstantial chance.

Semantics and various connotations

The semantic field of Serendipity comprises words like imagination, strolling, surprise, intuition, revelation, novelty and happiness.

Whereas algorithm is defined by calculation, method, programming, precision, formalization, repetition, sequence and explicable.

Everything is amazing when we talk about Serendipity!

In particular, with Voltaire, in 1748 and his philosophical tale “Zadig or Destiny”, inspired by the same Persian tale “Voyages and Adventures of the Three Princes of Serendip”. Walpole read Voltaire, since the French philosopher was a real 18th century rock star. Voltaire considered Walpole’s sagacity rather as a “rational discernment” and the circumstantial accident a “quirk of Providence”.

In particular, with Voltaire, in 1748 and his philosophical tale “Zadig or Destiny”, inspired by the same Persian tale “Voyages and Adventures of the Three Princes of Serendip”. Walpole read Voltaire, since the French philosopher was a real 18th century rock star. Voltaire considered Walpole’s sagacity rather as a “rational discernment” and the circumstantial accident a “quirk of Providence”.

Nowadays, it seems that the “quirk of Providence” has been replaced by ubiquitous algorithms and statistical models.

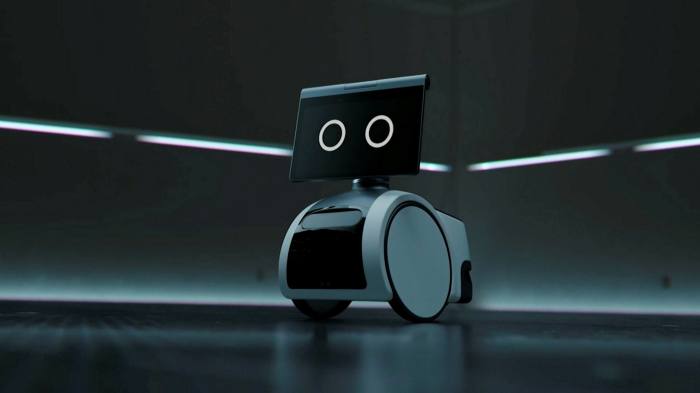

We can no longer deny the hypertrophied importance of algorithms punctuating our life, be it Siri, Alexa and other AI assistants. They accompany, assist, support and guide us on a daily basis.

Is it out of comfort? Lack of confidence? Too much confidence? Do we believe them to be superior to our own abilities?

Our relation to the world

Whether it is artificial intelligence, robotics, machine learning, deep learning or simply big data, it all prompts us to reflect upon the extent to which our relationship to the world, to others and to ourselves has been deeply affected by the governance of algorithms.

Does the free-style, non-programmed living still appeal to us in our ultra-calibrated lives? Calibrated by machines and algorithmic programs?

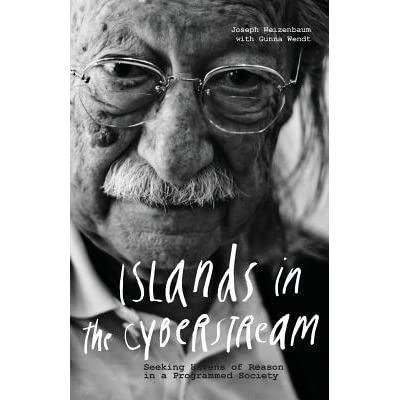

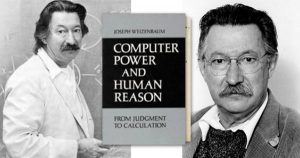

Observing the power of computers over humans is not new.

Already back in 1964, Joseph Weizenbaum (MIT), the pioneer of chatbots with his program Eliza, alerted of a possible misconduct.

In his book “Computer Power and Human Reason – From Judgment to Calculation” he pointed to a computational supremacy of programmed computers over Man. Over the psyche of Man.

Weizenbaum observed with bewilderment how “fast and deep” people fell for his simple script Eliza.

That the addiction to the computer program developed extremely quickly, putting the user’s common sense to sleep. Weizenbaum always insisted on considering ethical values like responsibility and trust in human-machine interaction.

And pointing to our power to choose, to judge that distinguish us from calculating and parsing machines.

For Weizenbaum humans decide, and machines calculate!

Serendipity has become bankable

Currently, Serendipity has become a hot topic in artificial intelligence and algorithms.

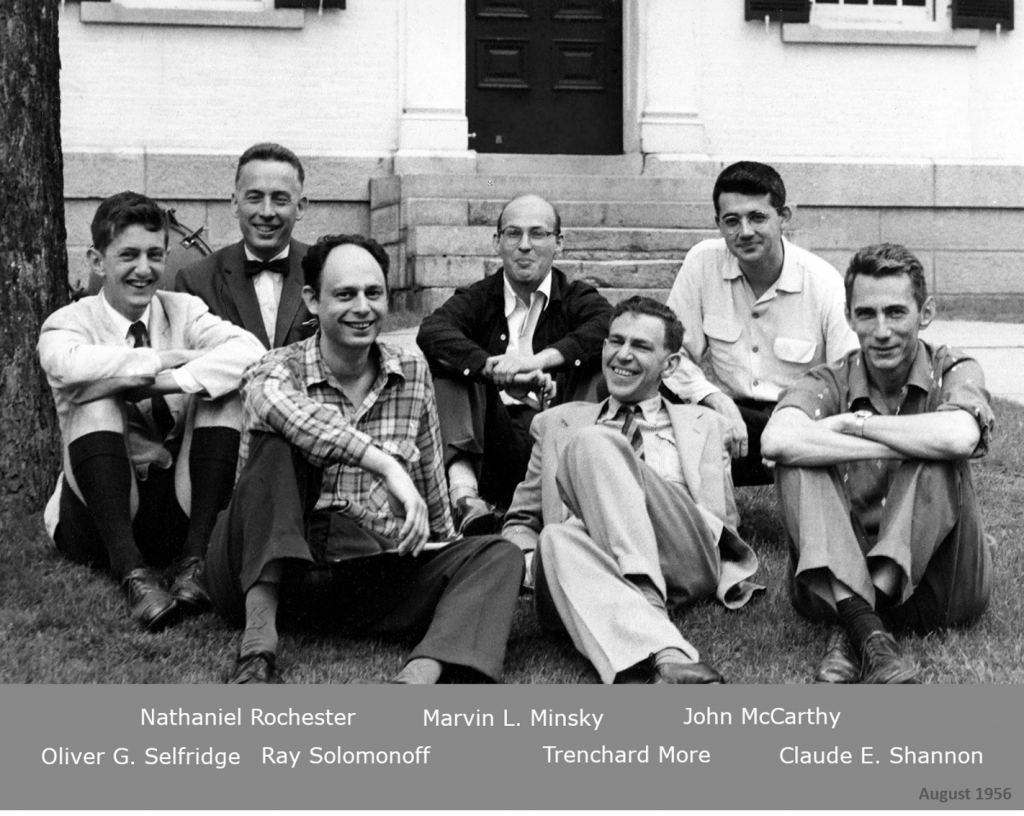

In terms of AI, the idea of Serendipity is not new.

It was present in AI laboratories since the 1980s. But the robotics and autonomous systems’ boom made Serendipity truly bankable.

Why now ?

Because ML models don’t match reality. They lack crucial human features like doubt and uncertainty.

Thus research by tech leaders in big data and artificial intelligence has centered for quite a while on injecting uncertainty into algorithms.

To artificially create vagueness. They would not call it Serendipity, but preferably “uncertainty”, “randomness” or “fuziness”. Creating AI systems that self-assess their own degree of uncertainty.

This field of research has become crucial for autonomous cars, military drones or medical diagnostics to better fit reality.

To mirror human thinking, doubting, evaluating, estimating before deciding.

The idea is to program, infilter the non-programmed in algorithms in order to make them more precise … in vagueness.

More realistic. More human. How paradoxical!

Abductive reasoning

When we address the delicate case of the inexplicable, the non-rational, Aristotle referred to a kind of logic besides induction and deduction we too often forget: abduction.

Abductive logic comes closest to explaining the phenomenon of Serendipity.

For Aristotle, abduction is a thought process using suggestion and supposition. Abduction is a logical method like deduction or induction – except that with abduction one does prefer hypotheses and possible explanations to actual observations.

“The car is wet.” So, it rained would be our deduction.

Except that this is just one hypothesis among many, not a proven conclusion.

With abduction one is certainly losing in rigor, but gaining in possibilities.

Abductive reasoning is used in many disciplines, such as medical diagnostics (it is possible that a symptom is a cause for a particular disease), the search for bugs in a technical or computer systems (if the computer does not start anymore , it may be that …), in the legal field and all kinds of everyday causal situations.

In the 19th century, the philosopher, logician, mathematician and founder of semiology Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) took a keen interest in abduction by “democratizing” it.

In the 19th century, the philosopher, logician, mathematician and founder of semiology Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) took a keen interest in abduction by “democratizing” it.

According to the American thinker, abduction “takes place in an uncontrolled part of our brain. The process has nothing to do with a logical rule ”.

Umberto Eco, describes abduction as “the detective’s method”. Looking for traces, detecting clues and formulating hypotheses. Exactly what happens when faced with Serendipity. We always want to solve the mystery of the inexplicable phenomenon that is to good to be true.

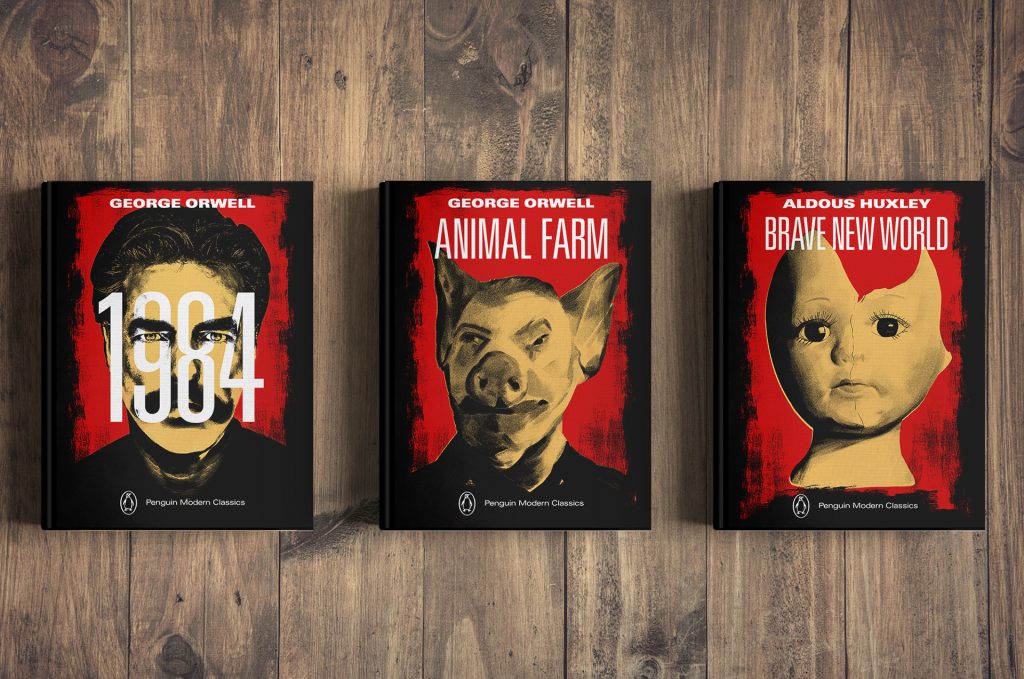

Binary algorithms cruelly miss out on humanity

Programmed reality forges / calculates a synthetic reality which sometimes becomes our lived reality.

A virtual reality sitting on artificial filter bubbles.

By excessive personalization algorithms lock us in narcissistic universes, formatted by our own knowledge and desires.

However our life is not an easy calculus or set of rules. It is our process of rationalizing that organizes it in sequential, logical and moderately predictable steps or episodes. But deep down, we are wandering in the unorganized.

The non-programmed, the unanticipated, the New, the unknown, the unexplained, the “Je ne sais quoi de presque rien” as Jankélévitch put it. Which is an integral part of our human condition.

If Serendipity brings us closer to reality, to truth, could we learn to live our life in a purely Serendipity style? Could it be a technique? An art?

Maybe Aristotle would answer “yes”. Just as Aristotle asserted that rhetoric is a technique, ethics is a lifestyle, maybe our mind, attitude, and perspective could make Serendipity possible in a continuous state.

How to live Serendipity?

Serendipity is undefinable. Unclassifiable, polymorphic and intense, like magic.

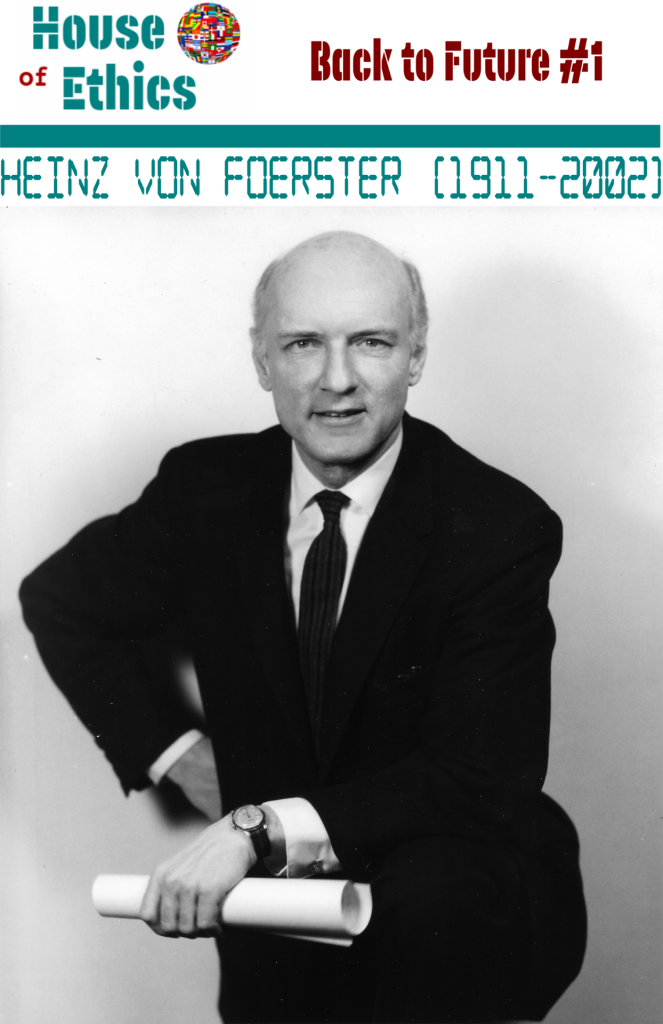

It is subjective and based on experiences. The extraordinary thinker and cyberneticist Heinz von Foerster might have used fractal. Like ethics. It repeats itself endlessly within itself.

Serendipity has no goal, while algorithms are computational processes assigned to a goal.

Could we live Serendipity daily? Let’s be realistic.

It appears that completely living our life in an unpredictable Serendipity mode would not be possible.

Yet doesn’t our human condition, our inner balance sporadically long for serendipitic moments?

Irrational, dadaist, fun and whimsical bubbles, intense at will.

Wouldn’t we miss out on life if we no longer could cultivate the unexpected?

Serendipity is genuine. Unique. Intense. Non-falsifiable. And it struggles to survive in an organized, arranged and logical world of algorithms. It loses its brilliance.

Maybe occasional radiant sparks of Serendipity are meant to counterbalance the algorithmic routine of everyday life that sometimes drags us away from our homeland: happiness.

To Find what you Were NOT Looking for!

If deductive and inductive approaches provide quantitative information partially contained in the premises, it is the novelty of the information that characterizes abduction, since it “brings us knowledge, fallible of course, but new”.

If deductive and inductive approaches provide quantitative information partially contained in the premises, it is the novelty of the information that characterizes abduction, since it “brings us knowledge, fallible of course, but new”.

Abduction is the provision of the fundamentally new, often irrational knowledge that characterizes Serendipity.

Like intuition, it is about envisioning the possible(s).

Serendipity therefore uses both perception and cognition.

The aim is to lead to a comprehensive understanding of an unexpected phenomenon: abductive suggestions strike us like lightning.

This is how scientists like Pasteur, Fleming, Roentgen, Schlieman or the Tatin Sisters discovered treasures without looking for them.

As algorithms take us further and further away from the possible and anchor us in a programmed real, Serendipity takes us to the other side of the river of possibles.

Serendipity or Algorithm - the book

This article is part of the book Serendipity ou Algorithme by Katja Rausch, published by Karà editions. 2019.

With contributions by Claudia Colombani, Panos Papadopoulos and Andrej Dameski.

- Founder HOUSE OF ETHICS

- Author's Posts

Katja Rausch is specialized in the ethics of new technologies, and is working on ethical decisions applied to artificial intelligence, data ethics, machine-human interfaces and Business ethics.

For over 12 years, Katja Rausch has been teaching Information Systems at the Master 2 in Logistics, Marketing & Distribution at the Sorbonne and for 4 years Data Ethics at the Master of Data Analytics at the Paris School of Business.

Katja is a linguist and specialist of 19th century literature (Sorbonne University). She also holds a diploma in marketing, audio-visual and publishing from the Sorbonne and a MBA in leadership from the A.B. Freeman School of Business in New Orleans. In New York, she had been working for 4 years with Booz Allen & Hamilton, management consulting. Back in Europe, she became strategic director for an IT company in Paris where she advised, among others, Cartier, Nestlé France, Lafuma and Intermarché.

Author of 6 books, with the latest being “Serendipity or Algorithm” (2019, Karà éditions). Above all, she appreciates polite, intelligent and fun people.

-

The proposed concept of swarm ethics evolves around three pilars : behavior, collectivity and purpose

Away from cognitive jugdmental-based ethics to a new form of collective ethics driven by purpose.