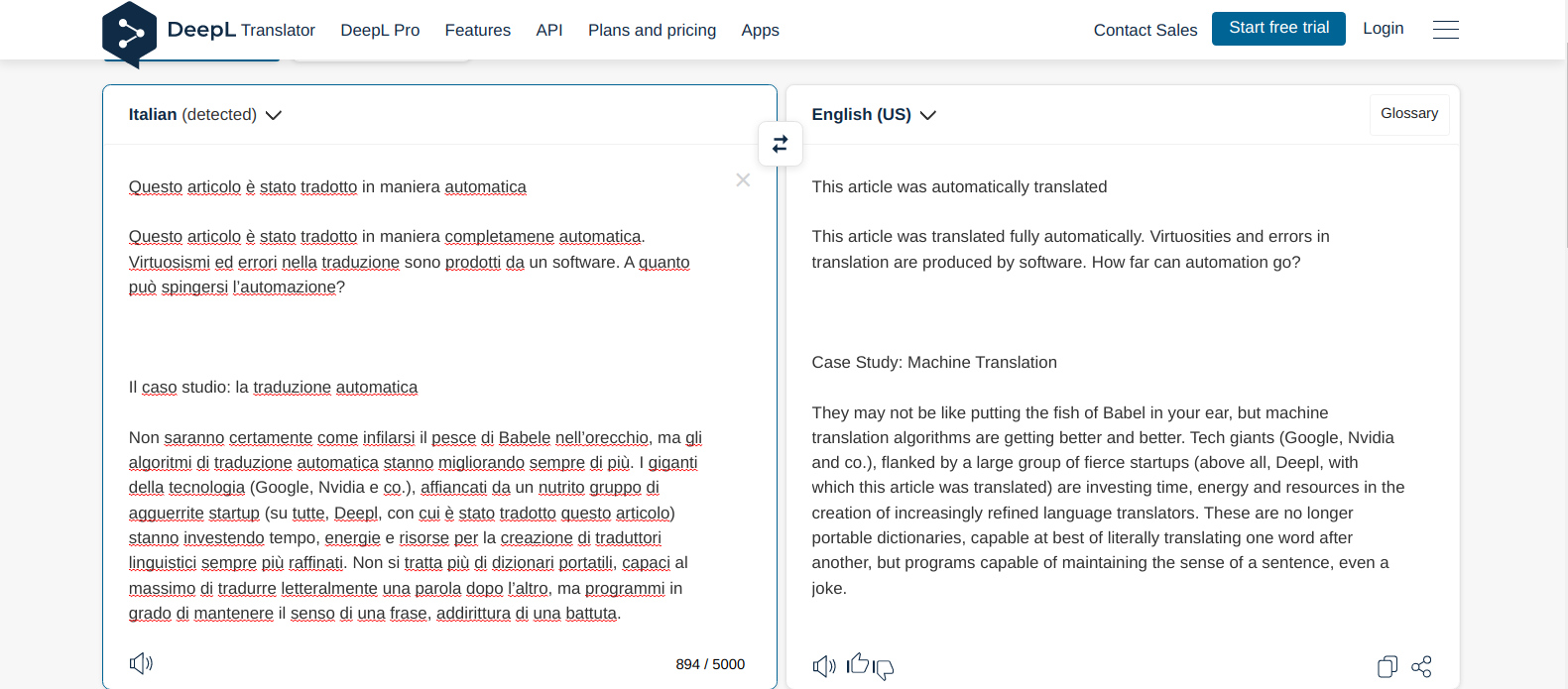

“Questo articolo è stato tradotto in maniera automatica — This article was automatically translated”

Questo articolo è stato tradotto in maniera automatica --- This article was automatically translated

Questo articolo è stato tradotto in maniera automatica (original text)

Questo articolo è stato tradotto in maniera completamene automatica. Virtuosismi ed errori nella traduzione sono prodotti da un software.

A quanto può spingersi l’automazione?

Il caso studio: la traduzione automatica

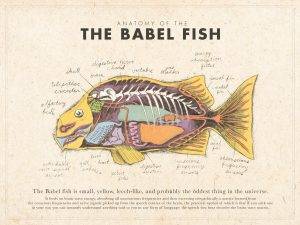

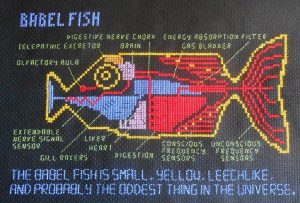

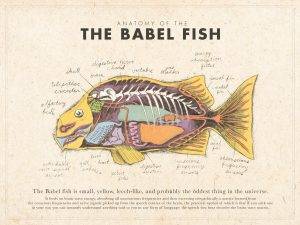

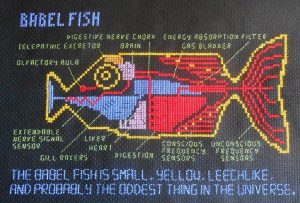

Non saranno certamente come infilarsi il pesce di Babele nell’orecchio, ma gli algoritmi di traduzione automatica stanno migliorando sempre di più. I giganti della tecnologia (Google, Nvidia e co.), affiancati da un nutrito gruppo di agguerrite startup (su tutte, Deepl, con cui è stato tradotto questo articolo) stanno investendo tempo, energie e risorse per la creazione di traduttori linguistici sempre più raffinati. Non si tratta più di dizionari portatili, capaci al massimo di tradurre letteralmente una parola dopo l’altro, ma programmi in grado di mantenere il senso di una frase, addirittura di una battuta.

Il campo di ricerca alla base di questi programmi è il Natural Language Processing. Frutto della collaborazione di informatici, linguisti e umanisti in senso lato, è uno dei campi interdisciplinari che sta facendo la fortuna dell’Intelligenza Artificiale. Alcune delle architetture informatiche più performanti sono infatti nate in questo campo, estendendosi poi al processamento di dati in altre discipline. L’ultimo ritrovato sono i cosiddetti Transformers, strutture informatiche capaci di dare “attenzione” a determinati elementi in una frase, estrapolarne l’importanza e, in linea teorica, ricostruire il contesto dell’intero discorso. Per completezza, va menzionato che, recentissimamente, i Transformers sono stati applicati con successo al processamento di immagini e alla ricostruzione di proteine (meraviglie dell’analisi dati!)

L’elefante nella stanza

I traduttori automatici sono ormai da tempo sull’orlo di essere venduti come sostituti umani, non solo come aiutanti. Una volta arrivati a un certo livello di precisione, dovrebbero – a rigor di logica – essere in grado di soppiantare i traduttori in carne ed ossa in molti compiti, allo stesso modo in cui i chatbot hanno affiancato i centralinisti. Eppure, non si registrano ancora applicazioni su larga scala degne di nota. La maggior parte dei servizi professionali si avvalgono comunque di personale umano per eseguire le traduzioni, o almeno per controllarle.

La ragione, ad oggi, sembra essere prevalentemente la precisione. Facendo una rapida ricerca su siti di diversi fornitori di traduzione, si nota che tutti tendono a rimarcare che le traduzioni eseguite da macchine non sono 100% corrette e necessitano di un intervento umano per raggiugere i livelli richiesti. Eppure, col costante miglioramento degli algoritmi, verrebbe da chiedersi se e quando avverrà il passaggio di consegne.

Non solo un problema di precisione

Le difficoltà dell’adozione unica di traduttori meccanici non stanno, però, unicamente nella precisione, ma sono difficoltà condivise con la maggior parte delle soluzioni di intelligenza artificiale. Si tratta di fiducia e responsabilità.

La fiducia sottointende, ovviamente, le aspettative sulla prestazione. Come da un’auto a guida autonoma ci si aspetta determinate prestazioni su strada, da un algoritmo di traduzione si desidera un’accuratezza a livelli umani. Dovrebbe sicuramente azzeccare tutti i vocaboli, ma anche rispettare la sintassi della nuova lingua, le sue strutture lessicali, magari le forme retoriche e, sicuramente, il contesto e i modi di dire. Ma, in senso più generale, manca ancora la fiducia che questi risultati possano venire raggiunti mediante l’analisi di miliardi di testi. Non è del tutto chiaro che schema statistico-induttivo dell’intelligenza artificiale possa riprodurre appieno ciò che un essere umano “sente”, “deduce” o “immagina” – proprio come non si ha ancora una vera e propria definizione per questi termini. Allo stesso modo in cui non traduttore esperto potrebbe non fidarsi di un nuovo arrivato perché “non ha il gioco della lingua”, così potrebbe mantenere riserve verso i traduttori automatici.

Responsabilità per le soluzioni tecnologiche

Il secondo problema è la responsabilità. In altri ambiti applicativi dell’intelligenza artificiale, quella della responsabilità è una difficoltà riconosciuta e dibattuta. Celebre è il caso studio di un’automobile a guida autonoma: dovesse trovarsi di fronte a un dilemma, come prenderebbe e giustificherebbe una decisione? Nel famoso “trolley problem”, un tram destinato a investire cinque persone legate sul binario può essere deviato in un binario parallelo, su cui giace una persona sola: cosa fare? Dilemmi di questo genere – meno sanguinari, forse – possono presentarsi anche in altre applicazioni, come la traduzione automatica. Dovesse venire riconosciuta un’offesa gratuita, la si tradurrebbe fedelmente? O, se fosse impossibile rendere fedelmente una struttura retorica o formale, bisognerebbe segnalare un’allerta, tradurla letteralmente, o procedere comunque? Le conseguenze diplomatiche, commerciali e interpersonali sono ovviamente riconoscibili.

In più, chi sarebbe da ritenere responsabile in caso di errore? L’utilizzatore, reo di non aver sorvegliato accuratamente il programma? L’azienda fornitrice, o i programmatori? Le risposte stentano ad arrivare per campi applicativi più sviluppati (almeno a livello di mercato o a livello mediatico, come le auto a guida autonoma), ma dovrebbero venire cercate in maniera generale, in particolare nel momento in cui le tecnologie dovessero uscire dalle loro nicchie tecnologiche e venissero utilizzate su larga scala e nei contesti più disparati

Per concludere

La questione di come approcciarsi ai prodotti di algoritmi automatici esula gli esempi più famosi e lampanti e permea ogni campo di applicazione. Sebbene apparentemente innocui e ricchi di promesse, anche i traduttori automatici non sono al riparo da difficoltà dovute alla fiducia traballante e ai vuoti di responsabilità che ancora esistono.

Come anticipato, questo articolo è stato tradotto meccanicamente da un originale in un’altra lingua. Dopo la traduzione, volutamente non è stato ricontrollato e corretto. Dovessero esserci errori o sorgere incomprensioni, l’autore si assume la responsabilità del proprio esperimento e sarà felice di rispondere alle domande dei lettori.

This article was automatically translated (translation)

This article was translated fully automatically. Virtuosities and errors in translation are produced by software.

How far can automation go?

The case study:

machine translation

They may not be like putting the fish of Babel in your ear, but machine translation algorithms are getting better and better. The technology giants (Google, Nvidia and co.), flanked by a large group of fierce start-ups (above all, Deepl, with which this article was translated) are investing time, energy and resources in the creation of increasingly refined language translators. It is no longer a question of portable dictionaries, capable, at the most, of translating literally one word after the other, but programmes able to maintain the sense of a sentence, even of a joke.

The research field behind these programmes is Natural Language Processing. The result of the collaboration of computer scientists, linguists and humanists in the broadest sense, it is one of the interdisciplinary fields that is making the fortune of Artificial Intelligence. Some of the best performing computer architectures were in fact born in this field, later extending to data processing in other disciplines. The latest invention is the so-called Transformers, computer structures capable of giving ‘attention’ to certain elements in a sentence, extrapolating their importance and, theoretically, reconstructing the context of the entire discourse. For the sake of completeness, it should be mentioned that, very recently, Transformers have been successfully applied to image processing and protein reconstruction (wonders of data analysis!).

The elephant in the room

Automatic translators have long been on the verge of being sold as human replacements, not just helpers. Once they reach a certain level of accuracy, they should – logically speaking – be able to supplant real translators in many tasks, in the same way that chatbots have stood alongside telephone operators. Yet, there are still no noteworthy large-scale applications. Most professional services still use human staff to perform translations, or at least to check them.

The reason, so far, seems to be mainly accuracy. A quick search on the websites of various translation providers reveals that they all tend to point out that machine translations are not 100% correct and need human intervention to reach the required standards. Yet, with the constant improvement of algorithms, one wonders if and when the handover will take place.

Not just a problem of accuracy

The difficulties of the one-size-fits-all adoption of mechanical translators, however, do not lie solely in accuracy, but are difficulties shared with most artificial intelligence solutions. These are trust and responsibility.

Trust subtends, of course, to expectations of performance. Just as a self-driving car is expected to perform on the road, a translation algorithm is expected to be accurate to human levels. It should certainly get all the words right, but it should also respect the syntax of the new language, its lexical structures, perhaps its rhetorical forms, and certainly its context and idioms. But, in a more general sense, there is still a lack of confidence that these results can be achieved through the analysis of billions of texts. It is not entirely clear what statistical-inductive scheme of artificial intelligence can fully reproduce what a human being ‘feels’, ‘deduces’ or ‘imagines’ – just as we do not yet have a proper definition for these terms. In the same way that a non-expert translator might not trust a newcomer because he or she ‘doesn’t have the language game’, so might he or she maintain reservations towards automatic translators.

Responsibility for technological solutions

The second problem is accountability. In other application areas of artificial intelligence, accountability is a recognised and debated difficulty. A famous case study is that of a self-driving car: if it were faced with a dilemma, how would it make and justify a decision? In the famous ‘trolley problem’, a tram destined to run over five people tied up on the track may be diverted to a parallel track, on which only one person is lying: what to do? Such dilemmas – less bloody, perhaps – can also arise in other applications, such as machine translation. If a gratuitous offence is recognised, will it be faithfully translated? Or, if it were impossible to faithfully render a rhetorical or formal structure, would one have to raise an alert, translate it literally, or proceed anyway? The diplomatic, commercial and interpersonal consequences are obviously recognisable.

Moreover, who would be held responsible in case of error? The user, guilty of not having carefully monitored the programme? The supplier company, or the programmers? Answers are hard to come by for more developed fields of application (at least at the market or media level, such as self-driving cars), but they should be sought in a general way, particularly when technologies break out of their technological niches and are used on a large scale and in the most diverse contexts.

To conclude

The question of how to approach automated algorithm products goes beyond the most famous and glaring examples and permeates every field of application. Although seemingly harmless and full of promise, even automatic translators are not safe from difficulties due to the shaky trust and accountability gaps that still exist.

As anticipated, this article was mechanically translated from an original in another language. After translation, it was deliberately not checked and corrected. Should there be any errors or misunderstandings, the author (and the House of Ethics; added by the editor) takes responsibility for his experiment and will be happy to answer readers’ questions.

- Director of Interdisciplinary Research @ House of Ethics / Ethicist and Post-doc researcher /

- Latest posts

Daniele Proverbio holds a PhD in computational sciences for systems biomedicine and complex systems as well as a MBA from Collège des Ingénieurs. He is currently affiliated with the University of Trento and follows scientific and applied mutidisciplinary projects focused on complex systems and AI. Daniele is the co-author of Swarm Ethics™ with Katja Rausch. He is a science divulger and a life enthusiast.

-

In our first article of two, we have challenged traditional normativity and the linear perspective of classical Western ethics. In particular, we have concluded that the traditional bipolar category of descriptive and prescriptive norms needs to be augmented by a third category, syngnostic norms.