BEYOND TRADITIONAL NORMATIVITY

Part 1 - Syngnostic Norms: Beyond Prescriptive and Descriptive Norms

by Daniele PROVERBIO (1) and Katja RAUSCH (2)

(1) Researcher in complex systems at University of Trento and Director of Interdisciplinary Research at The House of Ethics

(2) Founder of The House of Ethics – katja.rausch@houseofethics.lu

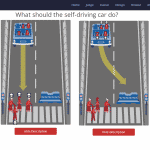

In cyber-physical times, an increasingly complex web of social and moral norms govern everyday personal and professional behavior and decision-making. We experience a multitude of different and conflicting norms and ethics, which coexist and collide at high speed and large-scale – from rules, to laws, to principles, to codes of conduct or netiquettes. Such norms are multi-source and explicitly or implicitly linked to cultural traditions, social institutions, religious beliefs, or philosophical frameworks. They help create social cohesiveness and support a system of shared expectations that shape identities, values and behavior at both a societal and individual level. But how to make sense of them?

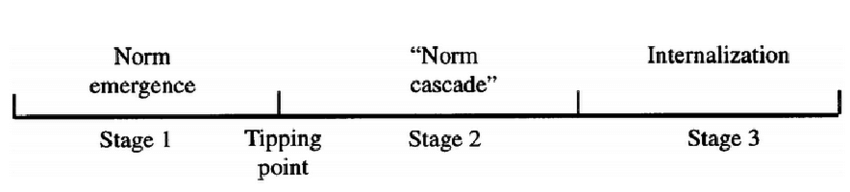

A long-standing concept is that of linear normativity (1); in this first article of two, we describe how it falls short in the digital age. We challenge the consequential three-phase process of norm emergence, cascade and internalization as described by Finnemore and Sikkink in 1998, relatively resulting in persuasion, socialization and conformity, proving it incomplete in cyber-physical times. In fact, it neglects typical systemic dynamics of non-linear hyperconnectivity, uncertainty and unpredictability of the so-called VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) world.

From early anthropology and philosophy, norms and ethics have been endemic to humans. However, both are social constructs (2) and thus subject to individual and collective dynamics influencing their emergence, transmission and adoption overtime, from individuals to small groups, to medium communities and large-sized societies, on- and offline. This article aims at clarifying the need to go beyond.

EMERGING NEW PATTERNS OF NORMATIVITY

Traditionally, the emergence of norms has been assigned to cognitive and individual-level small community interactions; only by the end of 1800, it began being described as a functional, society-level phenomenon and process (3). Overtime, a bipolar system crystallized into universal meta-norms shapers: prescriptive or descriptive norms.

Norms were initially considered a practical method of organizing members within groups, by attributing roles and effectively distributing resources to secure the survival of a social system. However, they now seem to fall short of their original connectedness to people. In liberal and open societies, they are progressively viewed as brakes and superspreaders of confusion.

The “primitive” character of norms has been overruled by latent “hyper-normatisation” as much as ethics has suffered from “hyper-instrumentalisation” – distancing both disciplines from people and purpose.

It resulted in counterproductive, confusing normative and ethical constructs overshadowing their original, organic, fluid and biological constituencies and effectiveness. But – luckily – it spurred empirically-oriented research directions with applied intentions to embed sustainability and governance at corporate levels (4).

This tension drove a body of modern research to suggest a return to the “original” approach by concentrating on people over concepts, observing how different classes of behavioral patterns arise and emerge beyond cognitive classifications and conceptualizations.

Key examples are the cross-cultural studies by Hauser (5) , the anthropological work on nonhuman primates by anthropologist Frans de Waal (6) , as well as recent digital anthropology findings by Boellstorff (7). The resulting novel, interdisciplinary and integrative landscape views emergence, transmission and adoption of norms and ethics as the results of collective interactions of beliefs, expectations, ideas and opinions occurring in an unpredictable, non-linear modus at high-speed and large-scale.

FROM ABSOLUTE TO INCREMENTAL

Similarly, traditional Western normative consequentialist, deontological and virtue ethics have been trapped in their own static and closed system, struggling to keep pace with complex and challenging modern digital times. Norms, social as well as ethical, have suffered from a gradual erosion of their absolute and universal status (8).

Nowadays, emerging and merging pluri-cultural and international cyber-physical networks, built on high-frequency connectedness, raise the question whether universal ethical and social norms are still at the epicenter of the so-called “global village”. (9)

In a world of data and patterns, multiple forms and formulations coexists and ethical debates move from cognitive and normative dissonance to “ethical dissonance” (10). Deviance or non-conformism are no longer understood as such but have become integral parts of opposing and contradicting realities coexisting in global and multi-normative nodes.

SYNGNOSTIC NORMS or “AGILE PURPOSE NORMS”

To offer a fresh perspective on the challenges discussed, we may look at the emergence of norms, social and ethical, as an interplay of cognitive and polysensory intelligences from a collective and decentralized perspective.

We pose the question of whether “breaking” norms bears significance in a transformational world, where merging and mixing turn into an integral step of “shaping” norms and create new patterns of fluidity and flexibility.

We thus argue that “traditional” and linear normativity is not enough, and that the traditional bipolar category of descriptive and prescriptive norms needs to be complemented by something more.

Beyond traditional prescriptive norms, which directs behavior by principles, and descriptive norms, that explain behaviour in practice (13), we suggest reshaping the bipolar nomenclature to a novel normative tricycle by including syngnostic norms. Normativity needs a novel category that focuses on behavior responding to “agile purpose norms”. Rather than focusing on top-down or bottom-up approaches, syngnosis focuses on the constant flux and updates from those two extremes.

Syngnostic norms embrace the idea of Gnosis (14), referring to human knowledge based on personal experience or perceived knowledge of humanity. In recognising the role of interactions, on top of individual status, it reflects the need to include hyperconnectedness, polysensory intelligence and collective intelligence in norms and ethics shaping. A syngnostic approach underscores the “shared interest in designing or, rather, in ‘meta-designing’ synergistic societies of the future. This quest is inspired by a need to care for the biosphere in a more respectful manner.” (15)

In practice, a “synergy of synergies”, which results in collective organic understanding where perspectives, values and norms cumulate into a new meaning, new norms, new ethics and new behaviours, instead of telescoping each other.

In this perspective, syngnostic norms naturally talk with the concept of Swarm Ethics (16). In the next article of Part 2, we will deep dive into this synergy, and discuss the profound implications for ethical thinking and actionable practice.

References

(1) Finnemore and Sikkink’s “norm life cycle”: Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. “International norm dynamics and political change.” International organization 52.4 (1998): 887-917.

(2) Proverbio, Daniele. “What if ethics does not exist?”. House of Ethics (2021), https://www.houseofethics.lu/2021/11/11/what-if-ethics-does-not-exist/

(3) Durkheim, Émile. “Les règles de la méthode sociologique.” Revue Philosophique de la France et de l’Étranger 37 (1894): 465-498.

(4) Seele, Peter. “Business ethics without philosophers? Evidence for and implications of the shift from applied philosophers to business scholars on the editorial boards of business ethics journals.” Metaphilosophy 47.1 (2016): 75-91.

(5) Hauser, Marc. Moral minds: How nature designed our universal sense of right and wrong. Ecco/HarperCollins Publishers (2006).

(6) de Waal, Frans HG. Primates and philosophers: How morality evolved. Princeton University Press (2006).

(7) Boellstorff, Tom. “Digital Anthropology” (2nd ed.). California: Routledge (2021)

(8) Panke, Diana, and Ulrich Petersohn. “Why international norms disappear sometimes.” European journal of international relations 18.4 (2012): 719-742.

(9) McLuhan, Marshall, and Bruce R. Powers. The global village: Transformations in world life and media in the 21st century. Communication and society (1989).

(10) Katja Rausch. “Ethical Dissonance”, House of Ethics (2023). https://www.houseofethics.lu/2023/09/13/in-search-of-the-ethical-dilemma-in-the-cyber-physical-age-from-ethical-dilemma-to-ethical-dissonance/

(11) AA.VV., “EU policymakers: regulate police technology!” (2023), https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Regulate-police-technology-EU-AI-Act-Statement-19-September.pdf

(12) AA.VV., “Open letter to the representatives of the European Commission, the European Council and the European Parliament” (2023), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1wrtxfvcD9FwfNfWGDL37Q6Nd8wBKXCkn/view

(13) Miller, Dale T., and Deborah A. Prentice. “The construction of social norms and standards.” (1996). Cialdini, Robert B., Carl A. Kallgren, and Raymond R. Reno. “A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior.” Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 24. Academic Press (1991). 201-234.

(14) Green, Henry A., “Gnosis and Gnosticism: A Study in Methodology”, Numen, Vol. 24, (Aug., 1977).

(15) Wood, John, and Otto van Nieuwenhuijze, “Synergy & Sympoiesis in the Writing of Joint Papers”, International Journal of Computing Anticipatory Systems, Volume 10, pp. 87-102, August 2006.

(16) Rausch, Katja and Proverbio, Daniele. “Swarm Ethics: A new Collective and Decentralized Purpose-Driven Ethics in the Digital Age”, House of Ethics (2022). https://www.houseofethics.lu/2022/09/23/from-swarm-intelligence-to-swarm-ethics-a-new-collective-purpose-driven-ethics/

Articles by D. Proverbio and K. Rausch

Spécialisée dans l’éthique des nouvelles technologies, Katja Rausch travaille sur les décisions éthiques appliquées aux domaines tels l’intelligence artificielle, la data éthique, les interfaces machine-homme, la roboéthique ou la Business éthique.

Pendant 12 ans, Katja Rausch a enseigné les Systèmes d’Information au Master 2 de Logistique, Marketing & Distribution à la Sorbonne et pendant 4 ans les Data Ethics au Master de Data Analytics à la Paris School of Business.

Diplômée de la Sorbonne, Katja Rausch est linguiste et spécialiste en littérature du 19ème siècle. Partie à la Nouvelle-Orléans aux États-Unis, elle a intégré la A.B. Freeman School of Business pour un MBA en leadership et enseigné à Tulane University. À New York, elle travaille pendant 4 ans pour Booz Allen & Hamilton, management consulting. De retour en Europe, elle devient directrice stratégique pour une SSII à Paris où elle conseille, entre autres, Cartier, Nestlé France, Lafuma et Intermarché.

Auteure de 6 livres dont un dernier en novembre 2019, Serendipity ou Algorithme (2019, Karà éditions). Elle apprécie par-dessus tout les personnes polies, intelligentes et drôles.

- Katja Rausch

- Katja Rausch

-