“Islands in the Cyberstream – Seeking Havens of Reason in a Programmed Society” by Joe WEIZENBAUM -fr

WE HAVE READ FOR YOU

"ISLANDS IN THE CYBERSTREAM - Seeking Havens of Reason in a Programmed Society" by Joe WEIZENBAUM

About "MECHANICAL MYSTIFICATION", "COMPULSIVE DEVELOPERS" and "ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENTSIA" !

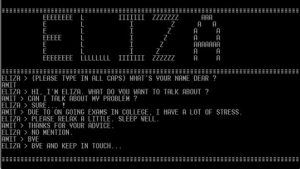

When talking about Computer Ethics, Joe WEIZENBAUM is and has been a leading light. Besides pioneering with his “chatbot” #ELIZA in the 1960s, he was totally visionary in his thinking.

What does set Joe WEIZENBAUM apart from other computer scientists ?

“Islands in the Cyberstream – Seeking Havens of Reason in a Programmed Society” was Joe WEIZENBAUM’s last book, in 2006.

Thus the book reads more like a philosophical manifesto by a computer #sociologist (not computer scientist! important) who early on, cautioned the deep impact machines, computers and computer programs have on society.

As always with brilliant people and visionary minds, la “grande histoire” reflects la “petite histoire”, meaning to more we know about the author’s life, the deeper will our understanding of his reflection be.

And WEIZENBAUM’s life was turbulent, at the least, as an immigrant from Nazi Germany (from Berlin to Michigan to Massachusetts) and a witness of major societal, political, and technological changes.

* Throughout his career, he was relentlessly pointing to the notion of “responsibility” and the harm of “COMPULSIVE DEVELOPERS” and the “ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENTSIA”.

* WEIZENBAUM believed that the issues involved were far too important to be left to computer scientists alone ! (hear hear)

* The first relevant observation is about the translation of the title : the original German title “Wo sind sie, die Inseln der Vernunft, im Cyberstrom ?” clearly identifies the nature of these islands. “Islands of reason” whereas in the English translation “reason” has been placed in the subtitle. (Important to mention)

* What does WEIZENBAUM set apart from his peers computer scientists? It clearly is his role as a sociologist. He casted himself a “SOCIAL CRITIC”, not a “computer critic “. He relentlessly cautioned against “MECHANICAL MYSTIFICATION”.

And that’s were we are TODAY. Still. Nearly 60 years later.

=> The first chapter of the book : “WE HAVE THE CHOICE”… opens up the distinctive reflection of one of the greatest minds in computer science.

Maybe we should humbly look back to think forward.

By the time of the interview Weizenbaum was 83 years old.

We have the Choice

Weizenbaum considers himself a social critic as opposed to a computer critic.

Dealing with the computer poses the question of value-neutrality. Working on computers is not a value-neutral decision.

The computer as a tool can be used for good or evi.

Weizenbaum reminds the reader that the computer was born during war and that the military made and sponsored nearly any research and advances.

There is no such thing like “autonomy of science and technology” nor “value-neutrality” for computers.

In each choice lies a value judgment.

Weizenbaum outlines the fact that most computers we come in contact with are hidden. He lists cars, TV, clocks. (And this was in 2006, way before the current boom of IoT with wearables, nearables and hearables.)

And most softwares being hidden amplifies our not being aware of potential dangers like unwanted data extorsions.

About the Computer History

In this chapter Weizenbaum traces the computer’s history back to military needs.

“It is completely clear that the vast majority of their research projects (MIT, where Weizenbaum taught) are funded by the Pentagon and will eventually serve military needs, even when that is more or less cleverly disguised. “

Agreeing on the brilliance of the human mind but insisting on the need to ask the question “With this great treasure, with the results of this extraordinary human endeavor, what do we do with it?”

Who takes Responsibility?

Weizenbaum reckons that denying responsibility is a wider phenonmenon than taking it.

“Responsibility is not a technical category, it is a societal one, and the current state of our society is characterized by denial of responsibility.”

Even more, technology distributes responsibility in a way so that no one has it!

As an example he cites Wernher von Braun and his book “I Aimed for the Stars” which Weizenbaum sarcastically completed with “but sometimes I hit London.”

Von Braun replied to this comments by “That’s not my department.” Period.

Being different as an Opportunity

As an immigrant boy and later scientist, Weizenbaum discovered his talent for mathematics and his liking for computers. But beyond that technical skill or talent, he pointed towards a specific trait of his character as being the catalyst for his being different and successful in computer science : humor.

“I don’t believe that I was smarter than other specialists, but I had among other qualities a sense of humor. So I could see the computer – and this is the important word – differently.

Humor gives distance. You have to be able to make jokes about yourself. He then adds : “I believe the joke is the most creative form of human expression. It is wonderful when you discover that you have made a joke. It is a great achievement.”

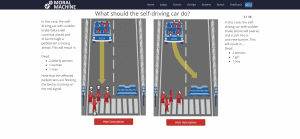

His computer program Eliza, the first chatbot, had been developed as a joke, to make people laugh! However people deeply and fastly fell for the computer program, which deeply shocked Weizenbaum.

To have invented Eliza, was one of the greatest regrets in his life, he later stated. Because he considered himself responsible for creating a negative impact on individuals and society at large, even if unwanted at first.

Islands of Reason

Weizenbaum recalls the many demonstrations against the Iraq war. All over the world people demonstrated. That in a world so many people with so many interests and origins demonstrated was evidence that there are “Islands of Reason”.

By “Islands of Reason” I mean a society of people with the goal to do good and to be humane. A community that radiates goodness and humanity.

Weizenbaum underlines the importance that even isolated islands can connect and have to connect.

“Admit to your ideas and show them to others” and you’ll eventually connect with like-minded islands.

Having been critical about MIT and MIT’s tight links to the Pentagon and military research, Weizenbaum often was asked why he did not leave MIT.

His answer :

“It was quickly clear to me that I served a certain function for MIT. […] There is Professor Weizenbaum. […] There were and are other colleagues. The most famous name I can immediately give you is Noam Chomsky.

The Illusion of Powerlessness

According to Weizenbaum each one’s behavior is key.

Everybody should act so responsibly as if the welfare of all humanity hangs in the balance.

What about powerlessness? What is the opposite? Weizenbaum concedes that there is no real opposite to powerlessness. It is not power nor strength.

“You don’t need to define something to be able to talk about it. Take Love. Would we argue then that it does not exist?”

Linked to powerlessness, Weizenbaum discusses the overuse of the modern word “problem”. And insists that not everything is a problem, and not all problems are equal, and do bear the recourse of an “expert”.

The Myth of Artificial Intelligence

When questioned what intelligence is Weizenbaum replies by referring to French psychologist Alfred Binet, the inventor of the “intelligence test”. Binet, when asked what intelligence were, used to answer : “Intelligence is what intelligence tests measure.”

Basically said, intelligence is relative to the intelligence of the test itself, the one who is designing the test, if he’s from the West, the East, his origin, his education, his motivation … There is no such thing as universality.

“Intelligence is not something of an objective size and no linear measurement of it independent of a defined framework is possible. Without a certain context, without a frame of reference, intelligence is meaningless”.

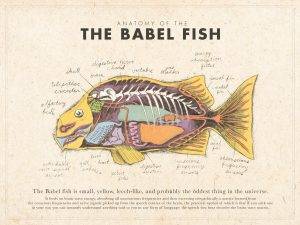

Plus, language can change the experience of reality.

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world” – Wittgenstein

As a subsequent question about “artificial intelligence” emanates “what makes a human human?

The dependence of each human on other humans. We humans cannot live in isolation.

Only a human can confirm the humanity of another human.

“In my thinking, that leads to this nightmare, this insane dream of artificial intelligence, to produce a machine, a robot, that becomes human.”

Here Weizenbaum refers to Mind Children by Hans Moravec where a complete person, as data points, can be transferred to a machine. If we “download” this information about ourselves it becomes “me”.

A kind of a post-biological age where DNA no longer plays a role. As a note, Marvin Minsky supported Moravec in his view that “the body is only jelly” and that “the human is an evolutionary mistake”.

Marvin Minsky being the one who coined with McCarthy, Shannon and Rochester the term “artificial intelligence” back in 1956 in Dartmouth…

Minsky for whom “The brain is merely a meat machine”. You can read the article “Artificial Intelligence : What if in 1956 Minsky, McCarthy, Shannon and Rochester named it machine by the House of Ethics.

Project Immortality

Mortality, meaning the role that human death plays in human life, as another key differentiator between human and machines.

What about the ever-present golem dream : we try to either build gods or become gods ourselves?

For Moravec, humans are weak, they get ill, are prone to accidents, are not that intelligent, and they die. Ultimate imperfection (!).

Today’s golem is a machine. And the machine is part of our social system. The system is embedded in society.

It is hard to turn it of. It is hard to point at one single responsible person. But there are group responsibilities.

“The computer only does what it is told” is not only wrong but rather dangerous. We shouldn’t accept that without resistance.

Already in 2006, Weizenbaum stated that the great globally active computer systems, in the military for example, cannot be seen through.

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett from Tufts University went that far as to say : ” We must lose our reverence for life before any real progress can be made in Artificial Intelligence.” Dennett has also his own views on human thinking and consciousness.

Here an excerpt on Consciousness and Free Will

Question: What is consciousness?

Daniel Dennett: Most people think consciousness, whatever it is, is just supercalifragilisticexpialidocious. It’s something so wonderful, wonderful, wonderful, wonderful, that we have to sort of divide the universe in two to make room for it. All in one side, all by itself and I understand why they think that and I think it’s just wrong. It is wonderful. It’s astonishingly wonderful but it is not a miracle and it isn’t magic. It’s a bunch of tricks and really is I’d like the comparison with magic because stage magic of course is not magic, magic. Its bunch of tricks and consciousness is a bunch of tricks in the brain and we’re learning what those tricks are and how they fit together and why it seems to be so much more than that bunch of tricks. Now, for a lot people the very suggestion that, that might be so is offensive or repugnant. They really don’t like that idea and they view it as in a sort of an assault on their dignity or their specialness and I think that’s a prime mistake. It’s a mistake because it means if you think that way, you’re going to systematically ignore the pads of the pads of exploration of research that, that might tend to confirm that and you’re going to hold out from mystery, you’re going to hold out for more specialness and it’s really there and some people just can’t help themselves. They can’t take seriously. They won’t take seriously. The idea, the consciousness is an amazing collection of sort of Monday and tricks in the brain. And they say, “I just can’t imagine it” and I say, “No you won’t imagine it. You can imagine it. You’re just not trying.”

Man and Machine

Intelligence? No! Power of the computer!

“Today the most perfect chess game a computer can play is completely and without exception the product of raw computer power. It has nothing to do with artificial intelligence.”

“The general public has been bombarded with computer myths and fairy tales.”

Who understands Who?

To the question whether computers “understand”, Weizenbaum, uses an analogy to nuclear power plants.

Do nuclear power plants produce energy? No! They just transform, convert energy. The same for computers. Computers don’t produce anything. They cannot “understand”.

So, can computer trick us? No, because the computer does not know what tricking is. Tricking is intentional.

I believe on the whole it (note: computer understanding) is “no”, then without a doubt we must conclude that work on this subject is hopeless and senseless.

Virtual, relative, chaotic

When talking about the word “virtual” Weizenbaum stresses that the word has undergone linguistic changes. Nevertheless this always holds true:

“If you say A is virtually B, than at a minimum we know that A is not B. It is something else.”

Worthy to remember when talking about the virtual “world”…

“I believe using this word is almost training us to omit essential things. We need to be conscious of the moment of manipulation that is hiding there.”

It is about uses and misuses of words, like virtual, relative and chaos. We need to be aware.

Technology has become a mediator for real experiences, be it a camera, TV or computer screens. It fully is embedded in our daily life.

Virtual “experiences”. Going to a concert is not the same musical experience as listening to a song on YT, and thus not convey the same understanding.

About the Value of Experience

Experience is what most is missing to computers, machines, robots. And experience is what most defines our knowledge, our being human.

“Maybe robots can pick apart simplified versions of our sentences but it could not interpret them correctly because it wouldn’t have our socialization of life experiences”

Plus the linguistic connotative, symbolic, contextual, cultural references are missing.

Civil Courage

As responsibility is a central concept in Weizenbaum’s thinking, and ditching responsibility equals with “moral laziness”.

The mere question “What can we do?” is an example of moral laziness. Of moral comfort. Or moral evasion.

A lonely Island of Reason? For Weizenbaum, every individual counts.

“Every individual person who acts responsibly, humanely, is already a small island. That is what counts.”

For us there are few moments in life we have to decide Who am I? What do I want? Why am I here? What difference does it make?.

“When it does happen […] then it could be good that you are suddenly alone, especially the first phase of the decision process. Something that always amazed me is that these things are so obvious so that everyone can say, “Yes, dear Joseph, that is all true, but why are you saying it? Why do you keep on saying it over and over? We know that.”

It is simultaneously obvious that we do not know it or anyway we are not conscious of it, we don’t react to it.”

What does “Civil Courage” mean?

“It is widely held but a grievously mistaken belief that civil courage finds exercise only in the context of world-shaking events. To the contrary, it’s most arduous exercise is often in those small contexts in which the challenge is to overcome the fears induced by petty concerns over career, over our own relationships to those who appear to have power over us, over whatever may disturb the tranquility of our mundane existence.”