The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Bioethics judge medical data practices in times of COVID-19 ERA

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Bioethics judge medical data practices in times of COVID-19

COVID-19 created a Tsunami of medical data that needs to be managed and protected in secure repositories to be further integrated and analyzed ethically.

All research teams are in a race against time to find a dedicated solution to COVID-19. Coinciding with that many ethical and legal issues were surfacing and that increased the data privacy issues as well as falsification and misconduct.

On the other hand, this crisis reflects the commitment of the privacy enforcement authorities to develop pragmatic and ethical approaches to secure sensitive data in a way not to hinder the pandemic fight.

This situation raises important questions: To what extent the given data access rights should be required ? Who owns the medical and genetic data? Are data practices available for anyone? What about the biohackers?

Here, I would like to discuss those questions to highlight the medical data practices at three levels: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly concerning COVID-19. Firstly, I will list the optimistic ethical practices and emphasize their effect as a good example for data practices. Then I will openly mention one of the dangerous and bad examples of data practices (e.g. Data fabrication and falsification) that were recently detected by the bioethics community. Finally, the ugly side will be mentioned as a response to the data practices of biohackers.

The Good: Ensuring medical data privacy

One of the most urgent bioethical issues in the COVID-19 global pandemic is how to manage the unprecedented flow of sensitive medical data. Securing sensitive data is crucial and getting robust techniques for their sharing securely is not an easy task.

Policymakers need to share the data to shape healthcare policies and fortify global cooperation. Scientists also need to have access rights to combine efforts to repurpose the already existing drugs.

As a result, recent endeavours were suggested by different countries trying to harmonize data security and medical data sharing at safe and fast channels. However, some of those proposals were rejected to protect privacy rights. The legalisation committee in France rejected the modification of the emergency law to authorise any medical records for a limited period (6 months).

Likewise, the federal privacy commissioner in Germany rejected and strongly criticized the proposal to use telecommunications to track the infected citizens, get their locations and retrieve their medical records. Instead of that, the German government authorizes the health ministry to ask the patient to identify themselves and inform them about their contact and travel history.

Privacy enforcement authorities in many European countries suggested pragmatic solutions to managing the deletion and preservation of medical data.

In 2020, they published general guidance for data management to apply the privacy and data protection laws in the crisis. This guidance is based on a practical strategy that respects the medical data protection and privacy principles in a way that doesn’t hinder the essential front-line responses to COVID-19.

In 2020, they published general guidance for data management to apply the privacy and data protection laws in the crisis. This guidance is based on a practical strategy that respects the medical data protection and privacy principles in a way that doesn’t hinder the essential front-line responses to COVID-19.

Moreover, the European Data Protection Board and the Council of Europe declared that “the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Convention 108 do not hinder measures taken in the fight against the pandemic, but do require that emergency restrictions on freedoms be proportionate and limited to the emergency period”.

A dedicated report to contact-tracing apps was declared by The European Union Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) affirming the medical data protection rights.

As shown, those statements confirmed that medical data protection and sharing can be done hand in hand. They also ensure that any record that could violate the data protection should be grounded in law, be necessary and be proportionate.

The bad: Data fabrication and falsification

According to statistics, about 1220 studies on COVID-19 were registered on the international clinical trial registry site, Clinicaltrials.gov in May 2020.

In July 2020, 19 published papers and 14 preprints about COVID-19 were either retracted or withdrawn due to the data falsification, methodological issues, and concerns about the participant privacy issues.

With no evidence or real data to back up declarations, two elite medical journals retracted very high-profile COVID-19 papers in 2020 over data integrity questions.

The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) retracted two papers after the trove of patient data they all relied on was doubted.

The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) retracted two papers after the trove of patient data they all relied on was doubted.

One of those famous studies was only posted online as a preprint (It is no longer available). It described ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug, dramatically overcome mortality in COVID-19 patients, prompting increased use and government authorization of the drug in several Latin American countries.

The authors used the same data in another study to claim that taking certain blood pressure drugs, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, didn’t increase the risk of death among COVID-19 patients, as some researchers suggested.

The Lancet paper was like the last straw that brought this data under more inspection as it focused on the safety and efficacy of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, which raised a political and scientific debate, especially after Trump’s embrace of the drug.

Once this study was published, a large international outrage in scientific communities arose and the study came under attack by medical ethicists and domain experts who asked how such large data was collected and analyzed tens of thousands of patient records from hundreds of hospitals worldwide.

Bioethicists raised questions about the complexities of navigating patient confidentiality agreements.

Leigh Turner, associate professor at the University of Minnesota Center for Bioethics, describes the retractions as “unnerving and disturbing.” He said “The less access they have, the greater the chances that there will be errors, data fabrication, or outright fraud.”

Turner said that by publishing only the author’s retraction statements, The Lancet and NEJM “didn’t show any self-reflection, any introspection. They should have looked at what might have gone wrong in their editorial process.”

Fabrication and medical data falsification are both unethical and dangerous. Reporting such misleading information about drug safety and efficacy can exaggerate the problem and put people’s life at real risk.

Those bad practices can not be stopped at a periodical or scientific level. The biohackers can’t wait to test those false outcomes on their bodies and inject themselves with drugs and homemade COVID-19 vaccines. They also taught online courses to show how to recreate that falsification at home.

The Ugly: Appearance of garage solutions for COVID-19

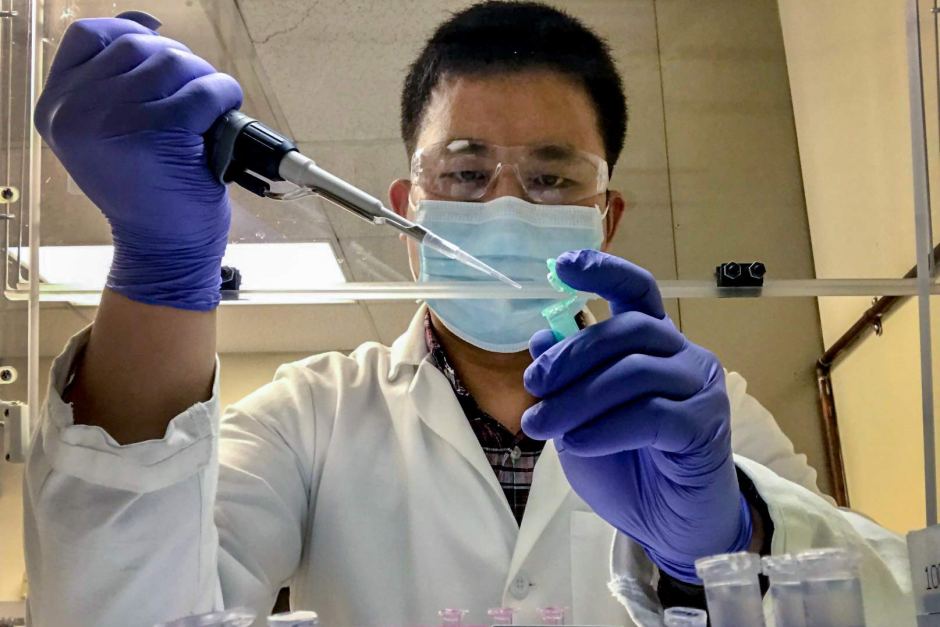

From testing kits to COVID-19 Vaccine production, biohackers left the mainstream science to foster the value of do-it-yourself home experiments.

In May 2020, when researchers published a paper about a DNA vaccine that increased the protective immunity against COVID-19, one of the biohackers saw an opportunity to recreate their methodology. The biohacker who worked before with the NASA found it easy to recreate the vaccine relying on the research trials on monkeys.

In October 2020, the biohacker tweeted “Our DIY COVID-19 DNA vaccine showed neutralizing antibodies in all three individuals. That was exciting but our goal was to teach people how to test expression in human cells, perform ELISAs &c. and that was also a success.”

Prof Henry Greely, the Stanford biomedical ethicist commented and said

“If he has and uses the appropriate biosafety precautions, I see nothing wrong with his efforts to replicate the macaque work in living human cells, If he can do that, it might be a somewhat useful scientific finding” and he continued, “It’s hard for me to see his administration of a vaccine to three people as producing any useful scientific knowledge, except perhaps in the unhappy result that they have terrible reactions to it. But even then, it’s just anecdotal, a caution but not a proof.”

Prof. Patricia Zettler, a former FDA attorney said, “So long as they only provide information about how to make a DIY vaccine, rather than distributing the materials to make one, Zayner’s efforts do not fall strictly under the regulatory purview of the Food and Drug Administration. However, the FDA has banned unproven and unauthorized COVID-19 products, and so these efforts might attract the agency’s attention.”

While the health authorities restricted COVID-19 research to the high degree biosafety labs, the biohacker taught an online course entitled Do-It-Yourself: From Scientific Paper to Covid-19 DNA Vaccine. He explained, “I want people to learn something from this, it’s no longer this big black box of what science, clinical trials and all this stuff is.”

A COVID-19 test kit is another example that was announced as the fastest and the cheapest test for COVID-19. The test’s creators are biohackers who intended to test on positive cases for COVID-19 to see whether positive cases get the same positive result.

They said, “We’ve been contacted by some hospitals and we’re being contacted by some people within response teams that should be able to verify our tests by running them alongside the tests that are already being conducted”.

Who ensures privacy and safety in that case ? To date, the test wasn’t approved by any of the health authorities, but if it is valid it will play a role in the testing capacity.

The data practices of biohacking may give good insights at restricted points but they don’t ensure safety and privacy. It is very dangerous to test high sensitive and infectious experiments at home. This can exaggerate the pandemic rather than control it.

To solve this issue, some questions need to be investigated by the ethical and legal community to find appropriate solutions : How should we go about biohackers pragmatically and ethically? What is the line between innovation and rejecting home-based experiments?

In conclusion, bioethics can maintain good data practices and also protect the medical and genetic data to be mishandled by the wrong hands. The ethical rules should also be updated from time to time alongside the pandemic and its medical precision. This will help to protect a specific population from the danger of bioterrorism and biological attacks based on tailored genetic or medical data. We can’t change our genome as we do with passwords but hopefully, we have Bioethics!

- Doctoral researcher in Bioinformatics

- Latest posts

My name is Ahmed Hemedan, I am a doctoral researcher at the bioinformatics core unit, LCSB at Luxembourg University. The research of my work covers a broad spectrum of applications of data science, bioinformatics and systems biology in the

life sciences. This includes the integration and interpretation of large omics datasets to the Disease Maps aiming to translate them into novel medical insights.

Furthermore, I use the revolutionary advances in artificial intelligence to develop machine learning-based paradigms to solve critical problems in medical research.

This resulted in a range of publications in peer-reviewed open access journals. Additionally, I use and extend the principles of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to make the research outcomes more personalized and FAIR.

I am advocating ethical approaches with all its facets (data, publications, source code of research software, etc) and I am active in communities promoting and implementing this for example The Carpentries community.

As a certified carpenters instructor, I try to empower biological researchers and librarians by teaching coding skills to work more efficiently and effectively with data, information and knowledge.

Contacts and links :

● Simply, send me a friendly email or If needed use my PGP key to encrypt the message. Find more crypto-goodness on keybase.

● ORCID identifier: 0000-0001-7403-181X further information/statistics regarding my publications can also be found on my Google Scholar.