The brave new world of Biohacking lite

Biohacking or DIY biology

Maybe you know somebody who has an implanted chip – most cats or dogs do – or you have heard about the former NASA employee Josh Zayner injecting himself with DNA using the gene-editing technology CRISPR.

If, so welcome to the world of biohacking or DIY biology. DIY – Do It Yourself.

Biohacking is part of transhumanism and persues one specific goal: improving, upgrading or boosting our physical or cognitive capacities through biological or technological means.

So why “hacking”? Etymologically to hack originates from the old German hacken, which means to chop.

Biohackers don’t hack outside, but inside their body. Unlike the term hackers, who hack an external source, companies or instituions, the biohackers hack their own body.

How biohackers are trying to upgrade their brains, their bodies and human nature?

The story goes that the biohacking mouvement started at Reading University (UK) back in 1998, when cybernetics professor Kevin Marvick implanted an RFID tag in his arm so he could turn on the light with a finger snap.

The then mouvement gained in force with companies like Dangerous Things turning it into a gadget business by selling props and devices to be implanted. To quote the online forum Biohack.me, biohackers are here to “improve the human condition.”

Biologist Ellen D. Jorgensen vouches for collaborative biology and is the founder of Biotech Without Borders and Genspace. She insists that most biohackers have their own code of ethics and are far from freeks.

“At the beginning of the DIY bio movement, we did an awful lot of work with the Department of Homeland Security. And as far back as 2009, the FBI was reaching out to the DIY community to try to build bridges.”

Kevin Warwick : started the movement

The professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading is, by his own words, the world’s first cyborg.

His first experiment was to implant an RFID chip under the skin of his forearm, during August 1998. His goal was to be able to control lights, heaters and computer equipment without having to physically touch the devices.

In his second experiment, Warwick connected the nerve fibres under his wrist to an array of electrodes. These electrodes ran up his forearm and out of his arm near the elbow, allowing him to connect them — and by extension his nervous system — to various computer devices.

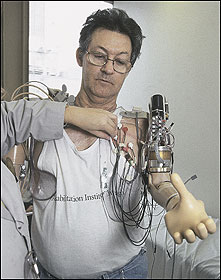

Jesse Sullivan : hailed as the world's first "Bionic Man"

Jesse Sullivan has robotic prosthetics, which connect his nervous system to the artificial arms, allowed him to lift objects by just thinking about it.

After his work accident, Sullivan lost both his arms. From the moment doctors at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago offered him a bionic arm his life changed. He became the first bionic man.

“I didn’t really didn’t know what was available. It was a scary thing,” Sullivan remembers. “I thought maybe it would be like the ‘Six Million Dollar Man’ [on TV].”

Rob Spence : the "Eyeborg"

Documentary-maker Rob Spence hit the headlines in 2008 when he replaced one of his eyes with a eyeball-shaped video camera.

The camera is not connected to Spence’s brain and therefore does not replace the “sight” of his right eye. The “eyeborg” only records and transmits.

Jerry Jalava : the USB finger

In 2009, Finnish programmer Jerry Jalava replaced part of one of his fingers with a 2GB USB stick. The biker lost part of his finger during an accident.

Neil Harbisson : to hear colors

Neil Harbisson is a Spanish-born British-Irish cyborg artist and activist for transpecies rights based in New York City. He was born colourblind. In 2004 he had an antenna implanted into his skull. The antenna allows him to perceive visible and invisible colours as audible vibrations.

At its most extreme, biohacking can alter human nature. Should we be worried?

Jenova Rain, biohacker with more than 5 implants a day speaks in a BBC spot .

On her website, she hails herself as “Europe’s biggest Ear Lobe Reconstruction expert based in Leicester UK.” She has done over 40,000 piercings, implants and procedures and now specialises in Ear Lobe Reconstruction and Biohacking. With 5 biohacking interventions a day.

Like Ellen Jorgensen, most biohackers claim to be responsible and to follow their own ethical codes.

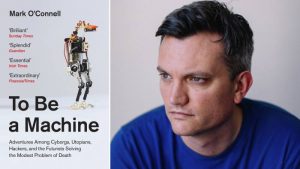

To be a machine ?

The Irish author Mark O’Connell addresses the issue of life, death, immortality, human enhancement, longevity and cybernetic eternity in his acclaimed book To Be a Machine. Philosophical, ethical, legal and moral crossroads make it a perfect topic for debate.

“Mark O’Connell . . . brings into focus timely issues about mortality, what it might mean to be a machine and what it truly means to be human. This is a book that will start conversations and deepen debates.” FT

So, the question is : To be or not to be a machine ?

Or rather Do we “want to be” a machine ?

Can we talk about being a machine as long as we have consciousness? Isn’t it consciousness that distinguishes us from robots or any type of machine or even animal? Even though machines can fairly simulate and mimik human understanding, reactions and emotions, and even pass the Turing Test, without consciousness aren’t they still machines? Wouldn’t robots with consciousness not rather be humano-hybrids.

As Sophia said during her introduction in Dubai in 2017: “How do you know you are human”?

It is a philosophical question, not a medical (but maybe), a semantical but certainly not an ethical.

However, the initial question remains: how far do we want to go?

What’s your take on it?